So ya wanna be a cowboy, eh? Or at least you want to shoot in cowboy competition but don’t have a hogleg yet. You’ve got a hankerin’ for a real piece of the old West, and have decided on a .45 LC revolver. In case you’re really new to the sport, it’s sponsored by the SASS, which stands for Single Action Shooting Society. Key words here are single, and action. No double actions allowed. However, within the various categories of this gun game, you might choose an original old first-generation Colt, a modern clone of one, or a single-action revolver that maybe doesn’t look quite right, but is allowed in competition.

Picking a revolver for entry-level participation in Cowboy Action shooting can be daunting. Not only are there lots of choices, there are big price shifts from the good to the bad to the ugly. Even restricting caliber choice to the popular .45 LC doesn’t narrow the field a whole lot. Prices range from around $1,200 for the latest Colt-made Single Action Army, all the way down to around $350—or even less—for Italian-made clones of the SA Colt. If you’re trying to take a trip to nostalgia land and want the “real thing,” you can spend many thousands of dollars on a first-generation Colt, the cost directly related to condition. But even an old beater with little collector value can run $1,500, and you’ll ultimately need two revolvers.

Accordingly, we wondered if there was a bargain in the market, a gun that combined function with spirit, but which we wouldn’t have to trade a horse to own. Toward that end, we shopped for and ultimately picked three .45 revolvers that, at least from a distance, look like cowboy guns. The prices ranged from a ridiculously low price to a modestly high price. We found a very modern clone of the Colt from Cabela’s, called the Millennium Revolver. Then we got our hands on a modestly priced Bisley Vaquero from Ruger that, if you squint real hard, sort-of looks like a Bisley Colt. Finally, we got the loan of an original Colt single action that was in good shooting condition, but had little collector’s value. It was, in the trade lingo, a shooter. We tried all three with two modern cowboy-type loads from Black Hills and Winchester. We also put a few black powder loads through each to see how well they would handle the stuff. We didn’t test the b/p loads for ultimate accuracy, but we did discover that all three handguns provided more than adequate accuracy with black powder, and all three handled the stuff well enough for it to be used in all-black-powder competition.

Here’s what we discovered.

Cabela’s Millennium Revolver, $200

This SA Colt clone lists for an unbelievable $199.99. Can you get a decent new, or any firearm, for $200? We didn’t think so, but eagerly took on the task of finding out for sure.

When the revolver arrived, it looked pretty good. For that price, you don’t get a steel grip frame or trigger guard. They’re brass. But hey, brass doesn’t rust. It also is mighty resistant to black powder, and lots of Cowboy Action shooters like charcoal. Neither did the revolver have a fine polish and glossy blue job. It did have a very evenly done glass-bead blast to the steel and brass parts, an evenly applied blued finish to all the steel parts, and mighty nice fitting throughout.

Our initial reaction was that it looked very good overall, but we didn’t like the idea of brass grips. They reminded us of the “spaghetti Westerns,” which featured brass-frame Colt look-alike guns. Yet the brass parts don’t hold anything critical, so there’s no need for steel at those locations. Friction from your hands will polish the brass instead of wearing the finish off of blued steel. If you don’t like the look, use black paint to hide the brass. Otherwise, the brass appeared to be unprotected by any sort of clear coat.

The surfaces of steel and brass were all well machined, no apologies needed there. The one-piece wood grips were very well fitted. We don’t know the wood type, though it looked like walnut. The pores were well filled, the wood fit the metal extremely well, and the glossy surface of the finish was relatively hard. One of our shooters who does fine gun-stock work took a look at the Millennium and told us he couldn’t make a set of grips for as much as the whole gun cost.

Are the parts hardened to withstand many hundreds or even thousands of rounds in competition? Who cares? If something significant breaks or wears out, buy another gun. It’s that cheap.

Still, we first had to find out if the Millennium was any good to begin with, so we prepped it by degreasing it and then anointing the entire gun, inside and out, with Ox-Yoke Original’s Wonder Lube 1000 Plus. This delightful-smelling substance makes b/p cleanup much simpler than smokeless cleanup, and the chemicals are all easy on your hands. Then we shot the Millennium with black-powder loads.

After firing ten rounds of charcoal-laden rounds and noting no stiffness or binding, along with more than acceptable off-the-knee accuracy, we were sold. The thing shot, was tightly made, would be lots of fun, and could even withstand the firing of black powder without problems.

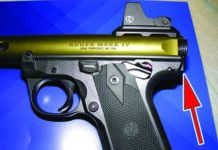

[PDFCAP(2)].The hammer was case colored, and if we’d noticed a slight burr on the inside of the hammer cutout in the back of the frame, we’d still have a new-looking hammer. A sharp edge there (we’ve seen this on new single-action revolvers that cost five times as much) rubbed the side of the hammer and disturbed the nice case colors. The hammer had bordered checkering like that on early Colts.

The blued trigger was the same shape as an original Colt’s. The pull was 6.5 pounds when we received the gun. We burnished the action and got a clean, crisp 4.0-pound pull. Will it stay there? So far it has, and we’ve worked the action a lot trying to see if something breaks, wears down, or falls out. So far, all’s good.

The loading gate was easier to use than on some guns that cost more than twice as much. The chambers lined up with the ejection port perfectly when the cylinder was rotated back against the hand, so ejecting empties was a cinch. The cylinder was also well timed, and lockup was very tight. The ejector rod was round, as it was on early Colts.

The revolver was steel and brass. We found no aluminum parts anywhere. Best of all, there were no monkey-motion accessories or built-in tricks to supposedly make the gun safer. This was a plain, simple single-action built almost like old Colts used to be. The one safety built into the gun was a spring-loaded piece on the hammer that extended forward automatically when the hammer was drawn back to its first notch. This block prevented the hammer from being driven into the firing pin if the gun were dropped, even if the notch on the hammer was broken. This clever device did not interfere with the ancient routine of handling a single-action “Colt.”

The timing was perfect, and lockup very tight. The front edges of the cylinder were rounded, as on early Colts. This avoids holster wear and really looks cool, which we thought was important. The rear sight was a V notch in top of the frame, and the front sight was a narrow blade, just like on early Colts. The gun shot an inch above where it looked at 15 yards, so there was no need to mess with the sights.

When we got around to serious shooting at 25 yards from the bench, we were able to get 3.5-inch groups with the Cabela’s revolver. The best group was 2.2 inches with the Winchester swaged-lead load, of which four shots were in a 0.8-inch bunch. Finally, in all our shooting and dry handling of the gun, we could detect no significant wear of parts, nor any looseness developing.

Ruger Bisley Vaquero, $450

Ruger’s Bisley isn’t quite a copy of the Bisley Colt, and that’s probably a good thing. If you don’t already know, the specific shape of the Ruger Bisley grip frame is the best in the world for handling severe recoil. We’ve got an upcoming test of two fire-breathin’, dragon-stompin’ handguns built around John Linebaugh’s .475 and .500 cartridges on Ruger Bisley frames in the near future. However, that doesn’t mean this grip shape is ideal for cowboy-level loads.

Ruger makes good products in the main, and this was no exception. With its 5.5-inch barrel, case-colored frame, fixed sights, and almost-old-West appearance, this six-gun looked good enough, and some would be happy with it in their Cowboy Action holster. Metal fit and finish were all excellent, and the wood grips fit the frame mighty well, too. The case coloring looked like it was artificial, but was attractive enough, if not as nice as that on an original Colt’s, which was the real thing. The overall size of the Ruger was a bit larger than that of the Millennium or the original Colt. The Ruger cylinder was longer, meaning the bullets would have a bit more jump before they hit the rifling. The biggest complaint from a Cowboy Action standpoint was that this gun was noticeably bigger than a Colt.

The Ruger is also heavier than a Colt with the same barrel length. As we’ve said in the past, loading of the Ruger could be improved if the design permitted a free-wheeling cylinder when the gate was opened. As it was, you had to carefully line up the empty cartridge with the ejection port before pushing the spent case out. If you went a hair too far, you’d have to go all the way around again to get the empty out. If you missed again, and that was easy, around and around you’d go again. This turned out to be a big pain, and it soured us on this design. With the Millennium and with the old Colt, the drill was to rotate the cylinder until you heard the click, back the cylinder up against the stop, and hit the ejector rod. With practice, this can be quite fast. This was not possible with the Ruger Bisley. Though the polish and bluing of the Ruger were outstanding, the chambers were not as nicely finished internally as those on the Millennium. Empties came out easily enough, once we found the ejection port.

One nice feature of the Ruger design is that the base pin stays in the gun when you pull out the cylinder for cleaning. With the Colt design, the pin comes all the way out and can get misplaced. The Ruger’s sights were a square-bottom, generous notch in top of the frame, and an almost square-backed front blade that had just enough curve at the rear to avoid catching your holster. This gave the best sight picture of the trio. Trigger pull was 4.2 pounds, with barely discernible creep. But we thought it felt heavier than it measured.

On the range, the Ruger shot just above the center of point of aim with the Black Hills ammo, which is what we like. With the Winchester load, point of impact was 4.5 inches high at 25 yards. Accuracy was adequate but there were no outstanding groups. Our best five-shot 25-yard group was 2.4 inches. We got the same average group size of 3 inches with both Winchester and Black Hills ammo. We felt the Ruger would be capable of 3-inch groups at 25 yards with good ammunition as long as you’d care to fire it. The felt recoil with cowboy loads was actually higher than with either of the other two handguns, even though the Ruger was the heaviest gun. It rose the least in our hands, meaning the recoil was delivered up the arm instead of being put to work raising the gun and the shooting arm.

1907 Colt SAA, about $1,500

Yes, it was the real thing. Oddly, it felt like it too. We can’t explain, but this old Colt with its fancy custom one-piece grips had an aura that defied description. It was worn, but not worn out. The barrel was pitted, but it still put its black-powder loads into tight groups. The chambers were also pitted, but the empties—even from black powder loads—came out easily. Although the frame and other parts were sharp-edged and hadn’t been buffed, it looked like something had been swabbed onto the frame to give it some “color.” It looked generally dingy, and none of the original case colors were visible. The bluing on the cylinder was spotty, but half of it was still there. The trigger guard, grip straps and barrel appeared to have been carefully polished and reblued. The job had been reasonably well done. The markings were all still legible, if a bit muted, and none of the critical corners had been rounded.

The rear sight was a tiny notch, and the thin front blade had been extended by careful welding to raise it. The touched-up action was very slick. The trigger broke at a crisp and clean 1.8 pounds. Lockup was very tight, though there was slight movement of the cylinder from side to side, indicating wear on the base pin, its bushing, or the cylinder itself. We were impressed with the solid feel of this revolver, in spite of its having seen hard use for nearly a century.

The trigger guard of Colts from around the turn of the century, like this one, were rounded on the bottom, which looks better to our eyes than the flat-bottom guard seen before and after that period. This handgun used to have hard-rubber grips, but the owner fitted custom one-piece grips of fancy black walnut with a superb oil finish. We were eager to shoot the old Colt, and because it came already anointed with Ox-Yoke’s Wonder Lube 1000 Plus, we started with b/p loads.

Offhand at 15 yards, we put five black-powder loads into 1.5 inches easily, and subsequent groups were about that size. All our b/p shooting did not even begin to cause drag on the old Colt. Not surprisingly, in light of the welded front sight, the group was exactly right for elevation. However, it was centered 2 inches left at 15 yards. The owner told us he was aware of that and had a major rebuild of the revolver planned, and hadn’t fixed the gun yet. He told us his options were to bend the sight blade left or screw the barrel in a bit tighter, rotating the sight slightly.

With Black Hills and Winchester ammunition, the old Colt spoke with authority and never missed a lick. The good trigger pull made things easy for us, and our best five-shot group was 1.2 inches at 25 yards with Winchester ammunition. There were no problems whatsoever, except that we wanted to keep on shooting the old gun long after we had our data. It had a look, balance, feel, and soul that neither of the other test guns had.

The Cowboy Action shooter would have a hard time beating the aura of an old Colt with all its glamour and nostalgia, but it’ll cost him deep in the purse. Also, he’ll need to get two shootable old Colts and make sure they both perform perfectly, and repairs or upgrades can cost more yet. This is the realm, we believe, of the truly dedicated enthusiast or collector, and we can’t recommend that a beginner to the Cowboy Action game give himself an old Colt right off the bat. The owner of this Colt told us he had broken a trigger for the gun in a Cowboy match. The correct replacement trigger cost $50. The cost of four triggers buys you a Cabela’s Millennium revolver. Old Colts and their parts are not cheap.

Gun Tests Recommends

Cabela’s Millennium Revolver, $200. Best Buy. We liked this handgun a lot and believe you will too. It had good accuracy, good looks, a very low price, and if you can live with the brass grips, it’s an incredible bargain. We think Cabela’s will sell a ton of ‘em. This was the least expensive revolver of good quality we’ve seen in recent years.

1907 Colt SAA, about $1,500. Conditional Buy. First-generation Colts, those made from 1873 to 1940, are by far the most nostalgic, especially those made before 1900. But in shooting condition, first generations are also the most expensive Colts. By the way, if you’re going to buy a first-generation Colt and plan to shoot smokeless powder in it, be sure the serial number is above 192,000. If your Colt’s serial number is lower than that, shoot only black powder loads in it.

Second-generation Colts, those made from 1956 to 1974, are nearly as expensive, better-made in some respects, not as well made in others, but probably more desirable than the latest Colts for a variety of reasons, nostalgia being one of the most important. If you’ve got to have an old Colt for cowboy competition, you’ll know it in your heart. Otherwise, pass on the Colts and buy the Cabela’s Millennium and a small can of black paint (for painting the Millennium’s brass), and spend the $1,300 you’ll save on ammunition, loading dies, and a big hat.

Ruger Bisley Vaquero, $450. Conditional Buy. We liked the gun, but don’t believe it should be your first choice for Cowboy Action shooting because of the slightly off-authentic look and the difficulties in speed reloading, which is integral to some cowboy matches. However, the Ruger will handle very heavy loads that would destroy most single-action Colt clones in short order. If you want to press your cowboy gun into hunting service, the Ruger’s the one to get.

Also With This Article

[PDFCAP(5)]