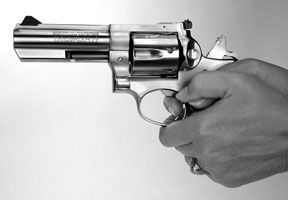

We recently attended a major sporting event where security was provided by uniformed police. We couldn’t help but notice how many officers, male and female were carrying revolvers instead of semi-automatic pistols. Never shy to interview, we took turns asking various officers why they had chosen a revolver. Here are some of the reasons they gave. “It can’t be knocked out of battery.” “The trigger doesn’t change after the first shot.” “I can get a really good action without worrying about reliability.” “It was easy to find a replacement grip that fit me.” “No mags to buy and this gun will last.” “It didn’t need any work to make it more accurate.” Most of the guns we saw were .38 Special/.357 Magnums, which offer a wide range of power without affecting reliability.

Those practical answers to self-defense problems moved us to evaluate currently available service revolvers from Taurus, Smith & Wesson, and Sturm, Ruger. The most popular barrel length in a service or duty revolver is 4 inches, and such guns are now widely available with seven-shot cylinders. Our Taurus Model 66SS4, $469, was a seven-shooter, and so was our Smith & Wesson Model 619 No. 164301, $646. Only our $615 Ruger KGP-141, a member of the GP100 family, was limited to six rounds.

How We Tested

There are many different types of .38 Special and .357 Magnum ammunition currently available. We decided to bypass frangible or other types of specialty rounds in favor of more traditional loads. First, we chose 148-grain lead wadcutters from Black Hills Ammunition. This is a classic target load, and in our opinion one of the most accurate over-the-counter rounds you can buy. Our choice of magnum ammunition consisted of American Eagle 158-grain jacketed soft point rounds by Federal, and Black Hills 125-grain jacketed hollow points.

Members of our test team collected accuracy data by firing each gun single action only from a sandbag rest at a distance of 25 yards. We documented our group sizes by taking measurements from center to center of the two widest hits inside a five-shot group. In addition, we fired standing unsupported at a cardboard IPSC silhouette target double action only from a distance of 7 yards. This part of our tests was performed with PMC 150-grain JHP .357 Magnum ammunition.

[PDFCAP(1)]

The purpose of our single-action test was to determine fine accuracy. The double-action test was designed to tell us more about recoil and trigger control. By engaging the target five separate times with two shots to the body and one to the head, we used the pattern of hits to help us evaluate rapid-fire capability. A rough or inconsistent trigger would likely force our shots low. A jammed cylinder would be even worse. Hard-recoiling ammunition forces the gun to shift violently to the rear. As the gun returns from recoil, the remaining ammunition and spent cases momentarily protrude from the cylinders. Should the cases not move forward before rotation is complete, they can catch on the breech face. Happily, none of our revolvers suffered an interruption in rotation.

We computed muzzle energy using the velocity of shots fired from all six (or seven) chambers of each revolver. At least one full day was devoted to shooting each gun. The Ruger revolver was shot under overcast skies that produced light rain. The Taurus was fired under a mix of clouds and sun. The Smith & Wesson revolver benefited from perfect shooting weather.

Here’s what we learned about each gun:

[PDFCAP(2)]

The Smith & Wesson Model 619 presented a traditional profile, but it contained some modern upgrades. The 619 was built on a round-butt stainless-steel medium-large L- frame. It had a full-length ejector rod. All but the tip of the ejector rod, which played a part in cylinder lockup, was left unprotected beneath the barrel. This reduced carry weight, but we think this also increased the possibility of damage to the ejector rod, which must turn freely for the gun to operate. The crown of the barrel was recessed about 0.15 inch from the muzzle to protect the final edge of rifling.

The front sight was a ramp design to prevent snagging. To reduce glare the front sight was grooved, and the upper surface of the barrel and the top strap of the frame displayed a matte finish. S&W machined the rear sighting notch into the frame.

Referred to as a Modern Style Smith & Wesson revolver in the owner’s manual, the firing pin sat inside the frame, and the flat face of the hammer struck the firing pin. There was a key hole located just above the cylinder latch that led to an internal lock used to freeze the hammer in place.

The trigger had a smooth surface, but we noticed ridges from the metal injection molding (MIM) process on it and the hammer. The MIM process produces parts that are true to specification right from the mold, reducing or eliminating time spent cutting, machining or trueing by stone. Given the MIM process was supposed to save time and money, we have to wonder why the 619 cost so much.

With the rubber Uncle Mike’s finger groove grip removed, we saw that power to the hammer was supplied by a leaf spring. Three screws held the side plate on to the frame. We removed the screws, and holding the gun by the barrel, tapped the butt of the frame with the grip of screwdriver, relying upon vibration to separate the side plate from the frame. With the side plate removed it was easy that why precision-made parts were so important to a smooth double-action trigger.

Shooting from the bench, our testers said the Smith & Wesson 619 had the smoothest single-action trigger of our three revolvers. All three guns required about 5 pounds of pressure to break the shot, but the release of the 619 was sheer pleasure. Still, despite its buttery-smooth let off, the 619 finished third, producing groups that averaged between 2.0 to 2.3 inches. Compared to most production semi-automatic pistols, this would be an enviable performance, but our other revolvers produced better accuracy. We think this can be attributed to the stark rear sight of the 619, which consisted solely of a notch at the rear of the frame. Adding an adjustable unit with a larger sighting surface would undoubtedly help accuracy. The advantage of the frame notch design was that it was nearly indestructible. We think a better solution than adding a full target or an adjustable sight would be to mount an Extreme Duty fixed sight from Cylinder & Slide, ($84, cylinder-slide.com). This is a compact, non adjustable, low drag sight that offers a high visual index. Paying attention to the height of the front sight blade the Extreme Duty sight can be tuned to your ammunition. As the 619 arrived, it delivered point-of-impact elevation for the 158-grain ammunition. The 125-grain JHP rounds hit about 3 inches below our point of aim.

In our double-action test, we had to slow down our shots to ensure accuracy. This was because after the cylinder was locked into alignment with the forcing cone, the final pull was rough and long. Pulling the trigger as evenly as we could, we were able to land seven of ten shots in the center of the target. In our opinion, the three shots low and left indicated how much trouble our shooter was having maintaining a constant point of aim throughout each stroke of the trigger. We were expecting a much better double-action trigger pull and wondered if the lock positioned next to the hammer was accounting for the loss in quality.

The Smith & Wesson shooter can get by with the service rear sight, but the double-action trigger was below standard, in our view. Most shooters tend to blame the use of MIM parts but according to Smith & Wesson the surface of MIM parts can be stoned and mastered to produce a fine action. We checked with Smith & Wesson (anonymously), and they informed us that if the trigger was out of spec they would indeed treat it as a warranty issue. To clarify they told us that by “spec” they meant that the single-action trigger should weigh 3 to 5 pounds and the double-action approximately 13 pounds. We measured the double action on our 619 to be about 15 pounds, so perhaps the factory would refine the trigger at no extra cost.

[PDFCAP(3)]

Ruger lists seven different models in the GP100 family with barrel lengths of 3, 4, and 6 inches. Finishes are either blued or stainless steel. Manufacturer’s suggested retail prices range from $552 for the .38 Special +P only models to $615 for the stainless steel .357 Magnum revolvers with barrel lengths of either 4 or 6 inches. All models come with a rubber grip complete with a rosewood insert. Our 4-inch barreled KGP-141 had a pleasing bright-stainless finish and an adjustable rear sight. Elevation was the familiar clockwise for down and counter clockwise for raising the point of impact. The windage adjustment required opposite movement for changing point of impact.

A second, very small screwdriver was required to turn the windage-adjustment screw. The rear-sight blade was partially protected from impact by riding back and forth inside the body of the unit. The rear notch was accented with white trim. The front sight on our Ruger was a black ramp grooved to reduce glare and dovetailed into place.

This is not the only feature on the Ruger revolver that distinguished it from our other test guns. The top of the barrel shroud was flat and grooved. The shooter pressed the cylinder release rather than slid it forward. The full-length ejector rod played no part in lockup, but a heavy detent mounted on the forward surface of the crane meshed with the frame. Weighing only about 2 ounces more than either the Smith & Wesson or Taurus revolvers, the Ruger featured a full-length underlug and overall gave the impression of being overbuilt. The cylinder lugs, for example, were deeper and wider than those found on our other guns. The grip was in fact a rubber sleeve that covered the butt frame that also housed the coil mainspring. It was held in place by a barrel-shaped lug captured by the rosewood inserts. The inserts had to be removed from each side and the lug pushed through before the rubber portion of the grip could be slid off of the frame.

All three guns had a distinct look, but the Ruger mixed squared edges, such as at the trigger and the hammer, with graceful sweeping lines on the barrel and behind the cylinder. The Ruger revolver did not offer an internal safety lock. A padlock designed to pass through a single chamber with the cylinder swung away from the frame was supplied.

The trigger on our KGP-141 revolver weighed in at about the same as our Smith & Wesson, but the feel was much different. The single action was smooth, but had a more pronounced let off. The Ruger double action was smoother from start to finish with the same felt resistance each time. Starting and stopping the cylinder produced little interference. This was followed by the smallest touch of stacking, which indicated the coil mainspring was fully loaded. Our shots fired double action formed the best group at center mass in our rapid-fire test. Four out of five shots to the head area formed the tightest group as well. From the bench our single-action-only shots averaged 1.7 inches firing both the hottest loads (the 125-grain magnums) and lightest, the Black Hills Match Wadcutters. But even in the case of firing the 158-grain .357 Magnum JSP loads, the difference between smallest and largest group was very narrow.

Given the fact that our accuracy test was performed under overcast skies with light rain, we would judge the sights on the Ruger revolver to be the best among our three guns. Due to the clear, rugged design of the sights combined with the consistency of the trigger, in both single and double action, we never lacked confidence firing the Ruger GP100 revolver.

[PDFCAP(4)]

In the hand, the Model 66 medium-frame Taurus revolver felt like the company’s Raging Bull guns, with their narrow grip and broad side panels. Most revolver grips offer a rounded profile, but we found it easier to hold the Taurus M66 more like a narrow semi-auto with our thumbs pointing forward instead of wrapping one over the other. This offered a natural index and helped us point the gun squarely at the target.

Our 66 revolver did not come with a ported barrel. This was a surprise because Taurus offers more ported revolvers than any other manufacturer. In fact, none of the eight revolvers listed as medium sized ranging in price from $375 to $484 on the taurususa.com website offer a ported barrel. All the Taurus revolvers, however, come with a key-operated popup lock that prevents the hammer from moving back when activated.

The finish on our revolver was a matte stainless steel that was understated but garnered much praise at the range. A blue-steel version of our test gun (66B4) lists for $438, but otherwise includes the same features. The 4-inch barrel with slightly recessed crown was treated to a full underlug. This shielded the ejector rod, which was capped on the end and did not play a part in lockup. Cylinder lockup was instead aided by a spring-loaded detent pin on top of the crane. The front sight was a ramp design machined as one piece with the barrel shroud. The visual surface was lined to reduce glare and also included an orange-colored insert. The rear sight was a fully adjustable unit with the blade positioned at the most rearward point of the top strap to maximize sight radius.

When we began shooting the Taurus, our shots were off target because the rear sight was adjusted to its lowest point and rode flush with the frame. This may have been to protect the blade during shipping, but when we turned the elevation screw to raise it the sight did not follow. We had to lift it free to meet with the bottom of the adjustment screw. After adjusting to the proper elevation, the sight unit could be pushed down against the spring detent and it would stick against the elevation screw.

Despite a lack of precision in the adjustment mechanism of the rear sight, the result from the bench was our best groups in the test. Firing the Black Hills 148-grain lead match wadcutters, we landed one group with all five shots touching. We measured this group to be 0.75 inches across. This came after we had ruined a 0.5-inch four-shot group by overpowering the trigger. Our average group size shooting the wadcutters was 1.3 inches. We registered averages of 1.7 inches and 1.5 inches firing the 125-grain and 158-grain magnum rounds respectively.

Our Taurus didn’t propel the bullets downrange as fast as from the Smith & Wesson or Ruger revolvers, but considering we were shooting .357 Magnum there was power to spare. Our staff agreed that the Federal American Eagle 158-grain JSP rounds were the heaviest-recoiling ammunition used in this test. The Black Hills 125-grain JHP .357 Magnum ammunition was louder and produced more flash, but proved softer in felt recoil.

Standing unsupported for our double-action rapid-fire test, the Taurus proved nearly as accurate and consistent as the Ruger revolver. The elevation of the group at center mass was as desired, but had a little more spread than the group produced by the Ruger revolver.

If the Taurus were to be used as a duty sidearm, we would replace the rear sight. Despite offering a good view we found that the sight can be moved out of alignment especially in terms of elevation. Furthermore, the overhang of the sight face left it prone to being damaged.

Gun Tests Recommends

Ruger GP100 .357 Magnum No. KGP-141, $615. Our Pick. The Ruger may only be a six-shooter, but we think it functioned with the most consistency and would likely offer the most durability. The front sight can be easily replaced and the adjustable rear sight was built to last. The ejector rod was shrouded, lockup was braced, and the GP100 shot with the least amount of muzzle flip.

Smith & Wesson 619 .357 Magnum No. 164301, $646. Don’t Buy. There’s an argument to be made that this gun should be a Conditional Buy, because, overall, it worked fine. But in our view, the Ruger simply outclassed it in sights, trigger, and accuracy. Also, the use of MIM parts was supposed to reduce cost, but the 619 was still higher priced than the other guns. The double action was as bad as the single action trigger was good.

Taurus Model 66 .357 Magnum No. 66SS4, $469. Conditional Buy. The Taurus offered a crane detent, seven-shot capacity and very good accuracy. But we’d replace the flimsy rear sight that looked good but took adjustment poorly and in our view wouldn’t last a week on the job.

Written and photographed by Roger Eckstine, using evaluations from Gun Tests team testers.