In 1959 a revolutionary rifle made its appearance. Designed by Armalite for the U.S. Air Force by Gene Stoner, the little rifle was designated the AR-7. It was chambered in .22 LR (high-velocity rounds only), and was unique in that it came apart without tools. Even better, all the parts could be stored within its hollow butt stock, and the rifle would float in either stowed or assembled form. When the rifle was made available to the general public, outdoorsmen of all sorts grabbed ‘em. At about the same time, the AR-7 made an appearance in the early James Bond film, “From Russia With Love,” and its place in history was thus secured.

We don’t know how many rifles have been produced, or what the overall commercial success of the AR-7 has been, but there must be a lot of these rifles out there. They’re still being made today by no fewer than two companies. Backing up a few years, Charter Arms acquired the rights to make the rifle from Armalite in 1973. In 1990, Survival Arms, Inc., acquired the rights and brought out a version with some design improvements. Today the AR-7 rifle is made by the Henry Repeating Arms Co., which offers its U.S.-made version with three finish options ($165-$200). It has the ability to store two magazines within its butt stock, not just one as in earlier AR-7s. Another company, AR-7 Industries, also offers the rifle ($150), and this company’s version also now stores two mags within the butt.

We acquired another interesting firearm, also touted to be a survival weapon. While some think a semi-auto .22 LR rifle is ideal for “survival” uses, others put their faith into multi-barrel firearms. One of the handiest, smallest, and lightest of these is the M6 Scout by Springfield Armory. This piece also has a military “survival” history. Springfield offers four versions. We acquired a stainless one in .22 LR/.410 ($219), and tried it against the two AR-7s in sub-freezing weather. What did we find? Let’s take a look.

Henry U.S. Survival Rifle, $165

We chose a black-finished rifle for our testing, and found the finish is actually Teflon. Other finishes are silver and (more costly) camouflage. The entire rifle weighed only 2.6 pounds empty, and arrived in a black cardboard box. Prying off the butt pad revealed three main component parts and two eight-round magazines. Assembling the rifle was easy and straightforward. The action fastened to the front of the butt stock with a captive screw contained within the pistol grip. The front of the stock was slotted to accept the receiver, and the action fit well and snugly into the recess. The barrel attached via a knurled ring to the front of the receiver. The magazine release was a lever at the front of the trigger guard, and it worked well, though the magazine was not as rattle-free as we would have liked. Speaking of rattles, the second magazine stored within the butt stock needed some cleaning patches or foam rubber to keep it from making unwanted noise.

There was a safety lever at the right rear of the action. It could only be put on (pulled rearward) with the gun cocked. It didn’t move easily. If we placed our thumb firmly on top of the safety, as its serrations and overall shape seemed to indicate was the thing to do, it was almost impossible to move it. But if the thumb were pressed against the forward or rear edge of the safety, the job became much easier. We found the same to be true of the AR-7 Industries version.

The Henry was matte-black finished everywhere except for the two magazines, which were blued, but shiny (we’d prefer them to be Teflon coated to match the rest of the rifle), and the butt pad, which was glossy black. The two magazines, bolt, extractor, trigger, and safety lever were of steel, and the action was an aluminum alloy. The bolt cocked via a tubular protrusion on its right side. That cocking arm moved in or out at the whim of gravity (same on both versions). This was not a problem, because the cocking arm may be ignored once the rifle has a round chambered. The extractor was a punch-press-made hook that rode within a slot on the right side of the tubular bolt. It worked very well, but we didn’t like the chewed-out appearance of its edge. Were we being too picky for a $165 rifle?

The Henry U.S. Survival rifle’s barrel was a steel tube encased within ABS plastic. The outside of the barrel was then coated with Teflon. The action was also Teflon coated. The finish was evenly applied and gave the rifle a rich, matte-black look. There was some waviness to the machining along the edges of the sight rail and around the trigger guard.

The finish on the Henry’s ABS butt stock was apparently sprayed on, and was slightly pebble-grained, and it gave a non-slip grasp. Unfortunately, during shipment of the rifle, some wear occurred on the right face of the stock, leaving a shiny area about half an inch in diameter, and we found it easy to enlarge that area with our fingernail — though that was not possible elsewhere on the stock.

The action was tastefully marked with “Henry Repeating Arms” over “Brooklyn New York” on the left side of the action. The right side had “Henry U.S. Survival” and the serial number, both of these beneath the ejection port on the action flat. A rear-pointing arrow indicated the “safe” direction for the safety. The thick trigger guard appeared substantial, and had enough room for use with gloves.

The barrel was keyed to the receiver so the front sight and extraction grooves would line up. One of our test crew had an early AR-7 that didn’t have an adjustable front sight. He achieved a slight lateral shift in impact by widening the snug-fitting barrel-key slot so the barrel could be slightly rotated. That is unnecessary with either the Henry Survival rifle or the AR-7 Industries version. They both had front sights that were driftable within a dovetail slot for windage. The front sight gave an ideal flat-top post as seen through the aperture. The bad news was that the Henry’s front sight blade could be easily moved with our fingers. Something would need to be done to secure it once your adjustments were made.

Elevation adjustment was accomplished by loosening a screw and sliding the aperture plate up or down within its dedicated groove in the rear of the action. We found sufficient sight adjustment to get the rifle zeroed with all our test ammo. We used the smallest aperture for all our bench-rest shooting, and it worked well enough. But as twilight approached, we found it progressively harder to see the front blade through that tiny hole. There was a second, larger, aperture at the other end of the plate, and we liked it better than the tiny one, and we didn’t seem to lose a lot of accuracy when we tried it. If the entire aperture plate were lost, there was still a big hole available for coarse sighting, and we found it served like a ghost ring. It might be the best choice in a gunfight because of its potential for great speed.

The rifle had a lively balance that was just right, despite its light weight. The barrel, though, was so light that it was more like a magic wand than a rifle barrel. Would it give magical results? So far, we were pleased with the Henry. It was time to shoot it to find out if it was worthy.

We first tried offhand shooting, and found the good balance let us hold this rifle easily enough. Hits were harder than they should have been, partly because of the stiff trigger and partly because of the light barrel. In the field every possible rest should be utilized, so the gun’s weight commonly plays a small part in most serious shooting, but a good trigger is vital. If we owned this rifle we’d fix the trigger pull. It broke at a hefty 6.5 pounds, though it was nearly creep-free. The bolt quickly became slick after a few shots had worn off the high spots. In our entire evaluation of this rifle we had two failures to feed with our test ammo, once with Stinger ammunition and once with Remington Yellow Jacket, which has a pronounced shoulder. The Yellow Jacket did not hang up on the bullet shoulder, but ran headlong into the receiver below the ramp. We were testing in sub-freezing weather, so it may be that the round was slightly stuck in a very cold magazine. We never had that problem again.

[PDFCAP(2)]The stock was man-size, and the pistol grip was larger in diameter than those found on most rifles. All who tried the rifle felt it was comfortable to hold and, except for the poor trigger, a joy to shoot. On the test bench, our best five-shot group at 50 yards was 1.3 inches with CCI Stingers. Stingers gave the best overall accuracy, but two other groups with Remington and Winchester ammo had four of the five in 1.5 and 1.6 inches, with a fifth flyer. The rifle was trying to shoot. We felt that a diligent search for the best ammo would pay dividends, but we’d be happy if all we had were Stingers.

We tried some standard-velocity fodder, actually two types of target ammunition that achieved around 1,000 fps in this rifle. That speed is significantly below what most standard-velocity rounds would generate. (By comparison, our test ammo developed from about 1,250 to nearly 1,600 fps with the similar-weight bullets.) Federal Gold Medal Match would eject 100 percent of the time, but the cycling bolt didn’t pick up about ten percent of the next rounds. But with RWS Rifle Match ammo, the Henry U.S. Survival AR-7 worked 100 percent of the time, fully reliably. One group put four shots into an inch at 50 yards, with a fifth shot making it a 2-inch group. We didn’t try standard-velocity or match ammo for serious grouping for many reasons, foremost of which is that serious survival/hunting ammo will mostly be high-velocity stuff. The Henry factory does not, by the way, recommend the use of super-high velocity ammunition in this rifle. Stingers and Yellow Jackets may be considered to be super-high velocity, but Stingers have proven to be useable in a great variety of all sorts of .22 LR rifles in our experience over the years, and have given the best accuracy in many of them, hence our inclusion of them in this test report.

We made sure the barrel was as snug as we could get it with our hands before testing, and also made sure the screw that held the action into the stock was tight. As noted, we used the sights that came with the rifle, but the receiver was grooved for common .22 LR scope rings. (The other version had the same setup.) We would suppose most serious users of such a survival rifle would make sure the iron sights were fine-tuned for the ammo of choice, and would use iron sights for all shooting. There would be nothing to prevent someone carrying along a scope in a day pack, which would increase the utility of this handy rifle, but would also increase the load.

We were very impressed with most aspects of this rifle, particularly by its versatility with low-velocity ammunition. We didn’t like the trigger pull, and would probably invert the aperture sight and use the larger hole in the other end for all our shooting.

AR-7 Industries AR-7, $150

Before we opened the heavy box that contained this rifle, we wondered what else was in there besides the AR-7. Opening it, we found the extra weight was from the all-steel barrel, which gave this version an empty weight of 3.5 pounds. While that’s only a pound more than Henry’s version, it represents a 40-percent increase. That’s a heck of a big difference. A hundred rounds of .22 LR Mini-Mags weighs 0.8 pounds, including its plastic case. Our version had an all-steel barrel, but the rifle is also available with an aluminum-covered, steel-lined barrel. The company’s website, www.AR-7.com, lists available options and accessories.

So what do you get for the extra pound of barrel and $15 less cost? Right off the bat, the overall finish of the AR-7 Industries AR-7 was better than that of the Henry. The extractor, obviously chewed out by a punch press on the Henry, was, in this version, a nicely finished part. The bolt, left in the white here, had clearly superior finish machining, as did the top of the receiver along the scope-mount rail. The two magazines fit more snugly into the action. The biggest obvious difference, besides the weight, was that we had the dickens of a time getting the butt cover off this version of the AR-7, indicating it might not leak as fast as the Henry’s, which came off suspiciously easily.

We decided a test was in order. We submerged both butt stocks under water in a sink for one minute, and then looked inside for leaks. We found significant water inside both stocks. So judging from our two samples, while your AR-7-type rifle may float, don’t wait too long to retrieve it. If you’re thinking the stock has enough buoyancy to keep the rifle afloat even if filled with water, you’re wrong. We stuck the open stock into a tub of water by itself, and it went right to the bottom.

This AR-7 had an all-steel barrel, except for the front sight and its base. The latter was milled out of aluminum. The sight itself was a non-ferrous casting. The Henry’s front sight was plastic. Compared to the “magic wand” feel of the Henry, this one felt like a club. Some of our test crew declared it was easier to hold the AR-7 Industries’ all-steel-barrel version on targets, from the offhand position, than was the Henry. But our consensus was that if the two shot equally well, we’d pick the lighter Henry version, because we’d use a rest in the field. Of course the plastic barrel of the Henry would stave off corrosion much better than an all-steel blued barrel.

The sight picture was essentially identical between the two, but we found it impossible to move the AR-7’s front sight by hand, as we could the Henry’s. The rear sight was again two apertures, tiny and tinier. The butt stock again had a pebble finish to it that appeared to be sprayed on, but it had no shipping flaws. The metal finish was matte black on the action, but semi-gloss on the blued barrel. This version also had glossy-blued magazines.

The exterior of the action appeared to be coated with a product similar to that used on the Henry. However, there was no information included with the rifle that told us anything. There was a target in the packing box, but nothing on the target told us the range, the ammo, or even the serial number of the gun (presumably the one on hand) that fired it. This, we thought, was amateur work, no matter how nice the gun looked. It was time to try AR-7 Industries rifle at the range.

The trigger pull was poor, measuring slightly over 7 pounds with some creep. The best group we fired was 2.0 inches, but it was achieved with great trouble using Remington Yellow Jacket ammunition, which did not feed at all reliably in this rifle. By comparison, the Henry digested it very well, and we checked this fairly extensively. The Winchester load gave a best group of 2.3 inches, but the Stingers averaged 2.4 inches for five shots at 50 yards, not what we’d hoped for. Trial groups with CCI Mini Mags went into 2.5 to 3.5 inches. We checked the tightness of the barrel and action and they were as good as we could get them. The poor trigger didn’t help. There was some indication of clustering a few rounds here and the rest over there, but no clear consensus of fine accuracy.

We tried the same brands of target ammunition that worked so well with the Henry, but a fired round would not even make it out of the chamber. We conclude you must use high-velocity ammunition with the AR-7 Industries rifle, and be sure your ammunition of choice works reliably in the gun before you need it.

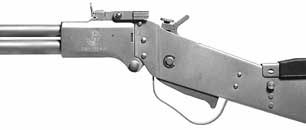

Springfield M6 Scout, $219

This break-action, over/under firearm is available in four versions, either stainless steel ($219) or Parkerized ($185), and with either .22 LR/.410 barrels, or .22 Hornet/.410. According to Springfield, their CZ-made version of the M6 is “improved and updated from the original U.S. Air Force M6 Survival Rifle.”

The first thing one notices about this firearm is that it’s almost all metal. Except for a rim of rubber covering the top of the butt stock and some plastic bits within the stock, the whole thing is made of sheet-metal stampings, castings, tubes, and other odd-shaped chunks of metal. On our “stainless” sample, most of the metal was non-magnetic except for the barrels, lock parts, latch mechanism, and the various pins. The overall appearance of the M6 was business-like, not really attractive but not really ugly, at least in part because of its form-follows-function design.

The gun was uniformly matte silver in color, the finish appearing to have been achieved by vapor-blasting. Metal work was more than just acceptable. We noticed some minor rust-like discoloration on the left locking lug of this “stainless” version. The left side of the action had the CZ logo, and “Czech Republic” beneath it. The right side held the M6 Scout designation, and also the name and address of Springfield Armory, and the caliber designations. The serial number was located beneath the action and also beneath the butt stock behind the trigger guard.

In our opinion, the trigger was not a happy device. It was a lever nearly three inches long with a serrated hook shape at its rear end. It seemed natural to insert one’s hand, or three fingers of it, entirely within the trigger guard, but that was perhaps not the best technique. We found that, in spite of the great amount of room within the trigger guard, the best system — at least with the rifle barrel — was to insert only the trigger finger into the guard, and press the trigger upward to release the hammer. This direction of motion was not quite natural, and in cold weather we noticed it a lot. Although the stock was long enough, the need to place the hand behind the long trigger guard put the arm into an almost cramped position, which took some getting used to. We discovered another problem with the trigger while firing the piece, which we’ll get to later.

The butt stock held a trap for fifteen .22 rounds and four 3-inch .410 rounds. The trap was opened by pressing hard on a button on the left side of the stock behind the trigger. The inside of the trap lid had a rubber cushion so the ammo within would be less inclined to rattle. There were two holes punched through both sides of the butt stock. We can only guess that the purpose was to provide a way to hang the gun onto a tree limb, or secure it with a rope or belt to the person carrying it. There was no rear sling-mount point, but there was a hole in the bottom of the front sight base that could accept a sling swivel, or a wire loop for a rope to carry the arm. The AR-7s had no provision for sling attachment whatsoever. The two barrels had enough room between them that it would be an easy matter to attach some sort of sling to the front end of the gun, and the shooter could use one of the two holes in the butt stock to attach a sling there.

There was a black-plastic checkered butt plate, which was actually an extension of the bullet trap hidden within the stock. The butt was curved, and stayed on the shoulder well enough.

The action opened via a serrated latch behind the rear sight. Lifting the latch permitted the 18-inch barrels and breechblock to swing open, revealing the two chambers. The latch worked very well, and felt natural and fairly precise. There was no looseness to the gun at the latch or hinge pin. The barrels swung through about 135 degrees, making the gun into a smaller package for easy storage and/or transportation. Even better, the hinge pin was easily removable without tools, making the gun into two pieces. Prudent users will carry a replacement pin, or even a suitable bolt to replace the hinge pin if it’s lost.

The upper barrel was a six-groove .22, with 1:15 inch twist. It would, of course, work with any .22 rimfire round from CB caps to Stingers. The lower accepted 3″ or shorter .410 shells, and was choked Full. A simple extractor between the chambers lifted rounds so they could be dumped out, or pulled out with the fingers. We found it necessary to pull the fired .22 cases out most of the time, and there was not enough room for frozen fingers to easily get at the fired case because of the close proximity of the action latch. Lifting the latch gave more room. This was not a weapon you could easily rapid-fire, but you could get off a shot from each barrel fast enough. Fired shot shells were harder to get out, and we resorted to using the rim of an unfired round to extract fired cases.

In front of the single hammer, and attached to it, was a three-position plunger. The top of the plunger was a small wheel, with serrated edges. When the plunger was in its middle position, it was possible to rotate the wheel counterclockwise, which moved a small finger into a locking notch. This was the gun’s official safety, but in fact the lowered hammer could not touch the firing pins unless the trigger were pulled, so the uncocked gun would be safe enough for most situations. Pulling the plunger up permitted firing the .22 barrel, and all the way down into the bottom detent would fire the .410. Several times we accidentally depressed the plunger as we cocked the hammer, and of course the rifled barrel didn’t fire when the hammer fell. We adopted the technique of cocking the hammer by grasping the plunger wheel with thumb and index finger, to make sure the plunger stayed in place.

The rear sight was a two-position arrangement, with an aperture for the .22 and a V-notch for the shotgun barrel. Windage adjustment was possible by loosening a small screw in the rear-sight base, and sliding the sight sideways in its dovetail slot. The front sight would have to be filed to regulate elevation. The gun hit low, so that was possible. The rear sight aperture was not centered within its standard, but the sight picture was good. We thought the aperture could have been slightly larger. The front sight appeared as a flat-topped post that we blackened for better visibility.

At the range, we found the M6 Scout shot .22s well enough. Its best group was with Winchester ammo, 1.6 inches for five shots at 50 yards. The all-metal design was not a problem in the cold because of the rubber-topped butt stock, and the fact that we wore a glove on our forward hand. As mentioned, the gun shot quite low, but we did not file the front sight. That is something its owner will need to see to, before expecting to hit anything with it.

The M6 Scout seemed to come into its own with shotshells. It hit exactly where it looked. Patterns were round, even, and tight enough to get some good out of the little shells. We’d guess that with the four shells contained within the butt stock, you’d have four grouse on the dinner table. We tried the gun against casually tossed snowballs, and as long as we kept the gun moving and worked the trigger with authority, we could get aerial hits. In fact we feel that triggering the gun with three fingers inserted within the trigger guard might be the better way to hit flying objects.

Finally, we tried some slug loads, and found they shot accurately enough to do some good against moderate-size game, as long as the shooter could get close enough to minimize shooting error and maximize the available power of the small slugs. We shot from a wobbly support, standing, and put three into a group just over three inches at 25 yards.

The balance of the gun was good, and we found we could do almost as well with this weapon firing .22s offhand, against the clock, as with the semiauto AR-7s. With sufficient time to work the long, odd trigger (and practice), the M6 Scout would surely put meat on the table in a survival situation.

We found one very annoying condition with this M6 Scout. Every time we slowly pressed the trigger for a careful shot, the hammer would make a small jump downward, as though it were falling. Then we’d continue pressing upward on the trigger and finally the hammer would fall. We felt this movement could induce a major flinch with inexperienced shooters.

The final choice of a go-along or “survival” firearm would largely depend on the kinds of game expected in the area, and the conditions under which you might expect to use the firearm. The .410 makes a lot more noise than a .22. Its ammo is heavier and much more bulky, but our shooters mostly felt a sense of confidence that the shot shells would guarantee food on the table more surely than a .22 rifle in a survival scenario, so we applauded the presence of the .410 barrel despite the added weight. Recoil was there with shot shells, but by no means objectionable.

If you knew you’d need the gun, you’d probably carry a good number of shot shells on your person, over the four in its stock. That is also the case with the AR-7s. But with unmodified guns, you’re guaranteed only 16 shots, just one more than the M6, with the ammo that would normally be contained within the AR-7. And with the AR-7 you don’t have those four shot shells. Yes, the M6 is a single shot rifle/shotgun, but for serious hunting, that may not matter a whole lot. And actually, it’s a two-shooter. If you see a flock of grouse, you could conceivably bag two with the contents of the barrels, which might be tough or impossible when the flock takes off after the first shot from your AR-7.

A .22 can kill a deer with head hits, and will kill sitting grouse. But shot shells might be better if you can’t hold steadily. If you’re wounded and desperate for food, that’s likely to be the case, and you’ll wish you had a shotgun because of its greater sureness of hitting something edible. For personal defense against human adversaries, the .410 would almost certainly be the better choice because of the intimidation factor of its shot barrel, but you get only two shots and then it’s reload time. There’s lots to think about in the selection of a survival firearm, and much of the decision depends on where you may find yourself and on your individual makeup, and is thus ultimately personal.

Gun Tests Recommends

Henry U.S. Survival Rifle, $165, Buy It. The fact that this rifle was so incredibly light was a big factor for us. We’d put a decent trigger into it and stick it in our backpack and go wherever we could legally carry a rifle, and consider ourselves prepared to fill the pot with nearly anything we could find to eat. The autoloader .22 will probably be a better choice than the M6 Scout if you happen to find yourself up against hostile forces. The Henry’s light weight would demand a steady rest of some sort in order to make reliable hits on small targets. We’d like more accuracy, but we felt this rifle had enough for most of its expected uses.

The leaky stock could be patched with tape, or maybe bacon grease, or we could tie the rifle to our belt with a cord whenever we got near open water. For that matter, we could carry the rifle on a lanyard around the neck, it was that light. This was not the case with the much heavier AR-7 Industries gun, as we tested it. We also would have liked to see a bit better workmanship here and there, but as we said, it worked well enough. That’s enough for us.

AR-7 Industries AR-7, $150. Conditional Buy. We could think of no reasons why anyone would want an all-steel barrel on one of these little rifles. It offered only added mass to the front of the rifle, and while that did help some of us in offhand shooting, a similar effect could probably by had by taping something like a box of ammo to the barrel of the lighter rifle. We liked the workmanship of this rifle. We didn’t like the fact that feeding wasn’t as good with all the ammo the Henry digested. While that doesn’t make us reject the rifle — it worked reliably with some types of ammo, and offered enough accuracy to be useful — it made us have grave questions about it. You’d save a few bucks, particularly at the street price, but we suspect you’d be happier with the Henry.

Springfield M6 Scout, $219. Buy It. We could not fault the M6 Scout, though we wish it had more of a shooter’s trigger. If we had a likely need to use the rifle for self-defense, the Henry autoloader may be the better choice. But if your needs include hunting with a light shotgun as well as with almost any .22 rimfire round except magnums, the M6 Scout should fill the bill. We liked its balance, ease of carrying, easy selection of barrel, accuracy, simplicity, and rugged construction. While it doesn’t make any pretenses at floating, it would be very hard, we thought, to break or damage it so that it would not be useful. The M6 was not so much a plinker’s delight as it was a serious hunting firearm. The more we used it the more we liked it, particularly because the .410 barrel shot perfectly to its sights and made excellent patterns. The variety of game that can be taken with the addition of a shot barrel was much expanded, and so was shooter confidence. That made us feel that, unless weight were the number-one item of importance, the M6 Scout would be preferable to the AR-7 for game-getting.