Drop-in cartridge conversion cylinders offer users the ability to shoot modern cartridges in percussion or cap-and-ball revolvers without modifications to the revolver. While it might seem similar to buying an aftermarket magazine for a semiautomatic pistol, it is more complicated with revolvers. What’s the expression? Timing is everything.

A cartridge-converter cylinder makes a cap-and-ball revolver more versatile and essentially changes it into a cartridge revolver. Loading cowboy cartridges is faster with a conversion cylinder than loading loose powder, wads, and balls into a percussion cylinder, but loading is still slower than a traditional single-action revolver. We wanted to see how easy it was to use a conversion cylinder, as well as the accuracy they could deliver. We also wanted to know how compatible the cylinders were among revolvers of the same manufacturer.

Two popular cartridge conversion cylinders are from Taylor’s & Co. and Kirst Konverter LLC. (KirstKonverter.com). Howell Arms provides the raw material for Taylor’s conversion cylinder, and Taylor’s cuts and blues the cylinders. The idea behind these cylinders is a shooter can field-strip a percussion revolver, remove the percussion cylinder, and install the cartridge conversion cylinder to shoot cartridges.

All new percussion revolvers are made by either Pietta or Uberti, and though the guns may look similar, they differ dimensionally. Specifications also vary between manufacturers. Parts from a Pietta Remington 1858 are not compatible with a Uberti Remington 1858. This means a conversion cylinder needs to be matched to the manufacturer of the revolver.

To learn the utility of the conversion cylinders, we used two 44-caliber revolvers, both Remington 1858 clones made by Uberti. One was a new Uberti Remington 1858 percussion revolver with the traditional 8-inch barrel, and the second was a new Taylor’s 5.5-inch barrel Remington 1858, also made by Uberti. We then sourced conversion cylinders in 45 Long Colt from Taylor’s and Kirst Konverter. We did not test the revolvers using the percussion cylinders; we only evaluated the conversion cylinders.

Though the revolvers are 44 caliber, their bore diameters are actually 0.451 inch and require a 0.452- to .454-inch-diameter bullet. This is the same bore diameter for a cartridge revolver chambered for 45 Long Colt, so good accuracy can be achieved using 45 Long Colt ammo. (As a side note, 36-caliber percussion revolvers have a larger bore diameter than the 38 Special cartridges used in conversion cylinders. Do not expect stellar accuracy using a 38 Special cartridge conversion cylinder for this reason.)

A few more caveats need to be mentioned before trying a conversion cylinder. Don’t use a conversion cylinder in a brass-frame replica nor an original percussion revolver because you will end up creating an IED that could destroy a gun or cause you and bystanders harm. Also, only use lead-bullet cowboy ammo with a conversion cylinder. This ammo is loaded to low velocities and low pressures and is perfectly safe in a new percussion revolver using a cartridge conversion cylinder. Also, do not use jacketed ammo with conversion cylinders. While these old percussion revolver designs use modern steel, the basic design is not strong enough to withstand the pressure from modern cartridges loaded with jacketed bullets.

Both the Taylor’s and Kirst conversion cylinders come in two parts, the cylinder and a back plate. The backplate is removed to load cartridges in the cylinder, and once loaded, the backplate is reinstalled. The complete cylinder is then installed in the revolver. After the cartridges are fired, the cylinder is removed, cases ejected, and then reloaded. The revolver, in essence, is field stripped each time the cylinder is loaded and emptied. Where the Kirst and Taylor’s cylinders differ is in the firing-pin design.

The Taylor’s back plate features six free-floating firing pins, one for each cylinder. This is similar to the set up on a percussion cylinder with six nipples, one for each chamber. The outer edge of the backplate is checkered for a sure grip when removing it from the cylinder. On the back of each conversion cylinder there is a stamp with either a “P” or a “U,” designating Pietta or Uberti, respectively. A small post protrudes from the back of the cylinder and aligns with a hole in the backplate. This ensures the backplate attaches the same way each time. The pieces are a tight fit. The rachet for the revolver’s hand or pawl is built into the backplate. Small notches are cut in the cylinder so you can see if an empty case or a round is loaded in the chamber. There are no safety notches on the cylinder, and Taylor’s recommends resting the hammer on an empty chamber if you plan on carrying the gun loaded.

The Kirst cylinder is named the Equalizer and the backplate is called a Konverter Ring, which features one spring-loaded firing pin at the 12 o’clock position. At the 6 o’clock position is a flat edge that fits into the cylinder window of the revolver’s frame. The ring or backplate does not rotate; it stays fixed. The racket is machined into a post that extends from the back of the cylinder. There is an open space between the ring and cylinder so you can see if a round is in the chamber. The cylinder has five chambers. You may recognize the Kirst Equalizer from the movie Pale Rider.

Kirst makes a ring with a loading gate, but you need to modify the frame of the revolver by cutting a loading port, an action that’s beyond the scope of this test. An ejector set is also available, and this replaces the Remington’s cylinder pin with a pin that has an ejector mounted to it. We did not test the gated cylinder or ejector set because permanent modifications must be made to the revolver.

The Taylor’s and Kirst conversion cylinders were nicely machined with a blued finish.

Both Remington 1858 revolvers operate the same way. They are single-action revolvers with fixed sights. To field-strip the Remington, unlatch the loading lever to allow the cylinder pin to be pulled to from the cylinder. The cylinder pin is captured by the loading lever so it can’t be dropped or lost. The cylinder is removed and replaced from the right side of the frame. We cocked the hammers numerous times with the percussion cylinder installed and controlled the forward movement of the hammer. You don’t want to dry fire on the nipples nor either of the conversion cylinders. The timing for both revolvers was fine with the percussion cylinder, and no ring formed on the cylinder even after extensive cocking of the pistols.

Ammo used consisted of 45 Long Colt ammo from Magtech and Sellier & Bellot. We also used 45 Schofield ammo, which is a shorter version of the 45 Long Colt. This ammo was made by Choice Performance. All of this ammunition is loaded with lead bullets to low velocities and is widely used by those participating in Cowboy Action Shooting, hence the reason they are generally called cowboy loads.

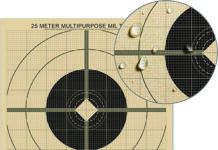

For accuracy testing, we used a range bag as a rest and set targets at a distance of 15 yards. For speed shooting, we used NRA D-1 targets, which are shaped like tombstones and the 8-inch bullseye and the 13-inch outer ring are perforations, making it difficult to see the rings. These targets test fundamental marksmanship and require the shooter to focus on the center of mass. These were set at a distance of 10 yards.

We checked cylinder/bore gap and used bore rods to check chamber/bore alignment. There is a learning curve with both cylinders when installing them into the replica Remingtons, as well as a few timing issues that were easily fixed.

Here’s what else we uncovered about using cartridge-conversion cylinders in cap-and-ball revolvers and the guns themselves.

Gun Tests Grade: A

$454

The 1858 Remington is the same as an 1858 New Army except this Taylor’s model has a shorter barrel. The balance is different between the two revolvers, but they operate the same. Fit and finish on the Taylor’s was very good. No ring formed on the percussion cylinder after extensive hammer cocking.

| Action Type | Revolver, Single Action, Hammer Fired |

| Overall Length | 10.8 in. |

| Barrel Length | 5.5 in. |

| Barrel Twist Rate | 1:18 in. |

| Sight Radius | 6.7 in. |

| Overall Height | 5.0 in. |

| Maximum Width | 1.6 in. |

| Weight Unloaded | 43.2 oz. |

| Weight Loaded Taylor Cylinder | 48.4 oz. |

| Cylinder Gap Percussion Cylinder | 0.006 in. |

| Cylinder Gap Taylor Cylinder | 0.005 in. |

| Cylinder Gap Kirst Cylinder | 0.001 in. |

| Capacity Taylor Cylinder | 6 |

| Capacity Kirst Cylinder | 5 |

| Frame Finish | Blued |

| Barrel/Cylinder Finish | Blued |

| Frame Front Strap Height | 2.5 in. |

| Frame Back Strap Height | 3.7 in. |

| Grip | Smooth wood |

| Grip Thickness (max) | 1.5 in. |

| Grip Circumference (max) | 6.5 in. |

| Front Sight | Fixed blade |

| Rear Sight | U-notch |

| Hammer Cocking Effort | 6.0 lbs. |

| Trigger Pull Weight | 3.6 lbs. |

| Trigger Span | 2.9 in. |

| Safety | Notch between chambers (percussion cylinder) |

| Warranty | 1 year |

| Telephone | (540) 722-2017 |

| Website | TaylorsFirearms.com |

| Made In | Italy (Uberti) |

The cylinder/bore gap of the Taylor’s percussion cylinder was 0.006 inches, the Taylor’s cartridge-cylinder gap was 0.005 inches, and the Kirst cartridge-cylinder gap was 0.001 inches. This is a good example of how tolerances vary between guns from the same manufacturer. The Kirst cylinder offered more muzzle velocity than the Taylor’s. We also figured that the small gap tolerance would mean leading might cause the cylinder not to rotate after extensive shooting.

We had the same issues installing the Taylor’s cylinder, but we did manage to get the hang of it after a few dozen tries. Once installed, it worked perfectly until a lead bullet gophered from its case, binding the cylinder.

Through the Taylor’s cylinder, the best accuracy with 45 Colt was with Sellier & Bellot, a group that measured 1.15 inches. The best 45 Schofield group measured 2.18 inches. As we noted above, one of the lead bullets from a 45 Colt cartridge was jerked out of the case during recoil just enough to bind the rotation of the Taylor’s cylinder. This required the revolver to be field-stripped and the round removed. We used a pen to eject empty cases from the chambers.

Gun Tests Grade: A-

$245

The Taylor conversion cylinder was tedious to install, but once in place, it worked perfectly.

Swapping the Kirst cylinder was faster and far easier. We also experienced a slight timing issue with this Taylor’s Remington clone, too. A slow hammer cock did not place the cylinder fully into battery, but a fast hammer cock did. This fast-cock trick allowed the Kirst to perform as expected, with no lead splash. As with the other Remington, the hand needed to be bent slightly for the Kirst cylinder to optimally function. The smallest 45 Colt group was with Magtechs, and that measured 1.92 inches. With the 45 Schofield, the best group was 1.27 inches. Velocity with the Kirst cylinder was 16 to 72 fps faster compared to the Taylor’s cylinder. The Kirst cylinder allows the user to either rest the hammer on an empty chamber or between chambers, to safely carry it loaded. There are firing-pin retainers between each chamber. We liked this feature.

Our Team Said: The short-barrel Remington had good accuracy, but we liked the longer-barrel Uberti version better. The Taylor’s cylinder worked, but we did experience a bullet coming loose under recoil, which is a result of the cartridge crimp and the recoil of a lightweight revolver. The Kirst cylinder is easy to swap out, but it required a slight timing tweak.

Taylor's Conversion Cylinder 45 Long Colt

| Magtech 250-grain LFN | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. |

| Average Velocity | 789 fps | 758 fps |

| Muzzle Energy | 346 ft.-lbs. | 342 ft.-lbs. |

| Smallest Group | 2.06 in. | 1.72 in. |

| Average Group | 2.95 in. | 1.82 in. |

| Sellier & Bellot 250-grain LFN | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. |

| Average Velocity | 901 fps | 810 fps |

| Muzzle Energy | 451 ft.-lbs. | 364 ft.-lbs. |

| Smallest Group | 1.31 in. | 1.15 in. |

| Average Group | 1.39 in. | 1.80 in. |

Taylor's Conversion Cyhlinder 45 Schofield.

| Choice Ammunition 200-grain RNFP | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. |

|---|---|---|

| Average Velocity | 855 fps | 845 fps |

| Muzzle Energy | 325 ft.-lbs. | 317 ft.-lbs. |

| Smallest Group | 1.05 in. | 2.18 in. |

| Average Group | 1.79 in. | 2.50 in. |

Kirst Konverter Conversion Cylinder 45 Long Colt.

| Magtech | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. | ||

| Average Velocity | 725 fps | 780 fps | ||

| Muzzle Energy | 292 ft.-lbs. | 340 ft.-lbs. | ||

| Smallest Group | 1.11 in. | 1.92 in. | ||

| Average Group | 1.81 in. | 2.08 in. | ||

| Sellier & Bellot 250-grain LFN | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. | ||

| Average Velocity | 859 fps | 882 fps | ||

| Muzzle Energy | 410 ft.-lbs. | 432 ft.-lbs. | ||

| Smallest Group | 2.07 in. | 2.65 in. | ||

| Average Group | 3.11 in. | 2.69 in. |

Kirst Konverter Conversion Cylinder 45 Shofield

| Choice Ammunition 200-grain RNFP | Uberti 1858 New Army | Taylor’s & Co. 1858 Remington 5.5 in. |

|---|---|---|

| Average Velocity | 875 fps | 861 fps |

| Muzzle Energy | 340 ft.-lbs. | 329 ft.-lbs. |

| Smallest Group | 1.90 in. | 1.27 in. |

| Average Group | 2.38 in. | 1.54 in. |

I have 2 outlaws in 357 magnum which are my favorite revolvers One is a 51/2 and the other is a 71/2.

No problem with the accuracy and the revolvers are great looking. One was from Taylor and the other from Uberti. In comparison to Rugers, I would rather have an Outlaw. The wood grips are the very best for a over the counter revolver. Could not get a better gun for triple the price.