Light-Recoil 45 ACP Loads

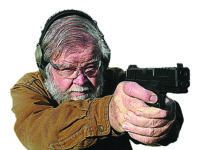

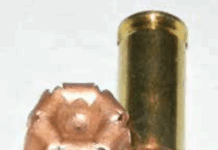

The road in life isn't always straight and narrow. It can be winding and even out of control. Some changes are unwelcome, even fearful. Among the significant changes as we age is a loss of muscle mass. Shooters who once handled hard-kicking handguns now find them ever more difficult to handle. Arthritis and a culmination of old injuries make firing the big-bore pistol difficult. These individuals, along with young shooters who have adopted a lightweight pistol such as a Colt Commander, and slightly-built female shooters interested in a low-recoil load, are faced with difficult decisions. Once the decision is made to take advantage of the big-bore 45 ACP handgun, shooters are seldom willing to back down to the 9mm.

High-Capacity 357 Magnum Carry Revolvers from S&W

Like so many other shooters, our evaluators like the 357 Magnum cartridge for defense as well as the flexibility of lower-recoil and lower-cost training using 38 Special ammunition. To see if we could find a bargain, we wanted to pit two expensive high-capacity snubnose revolvers in that chambering—the Models 327 and 627—and add into the mix a more traditional, affordable used six-shot snubnose, the Model 686 164231, which is no longer in current production but which is widely available from around $600 to $800.

The 6-shot Model 686 is the stainless-steel version of the Model 586, which debuted in 1981 and was one of the first L-frame or medium-sized revolvers offered by S&W. The L-frame guns are slimmer and lighter than the hefty N-frames. Both the Model 586 and the Model 686 were immensely popular with law enforcement, outdoorsmen, competition shooters, and home defenders. The 586 went out of production but was reintroduced a few years ago. The Model 686 is a pure S&W classic that is able to withstand continued use of 357 Magnum ammo. We have reviewed the 686 in various configurations in past issues, such as the 2.5- (No. 164192, Grade A January 2002), 4- (No. 164194, Grade A March 2007), 6- (No. 164224, Grade A- March 2011), and 8.4-inch (Grade A February 2001) barrels and the Plus variant (M686-6, Grade A January 2002), which has a 7-shot capacity, and all have been excellent revolvers. We have also reviewed the Model 327 in the past (Grade B February 2005). The snubnose revolver new to our team is the Performance Center Model 627.

Smith & Wesson introduced the first, the original, 357 Magnum revolver in 1935 known as the Registered Magnum. S&W chose to chamber the powerful 357 Magnum cartridge in a six-shot revolver built from the company's large, heavy-duty carbon-steel N-frame. Almost immediately, the Registered Magnum was adopted by the Kansas City Police Department, and other LE agencies soon followed. To say the revolver and cartridge combination was successful is an understatement. When introduced at the height of the Great Depression, the revolver cost $60 — nearly a king's ransom in those days. Yet Smith & Wesson had a hard time filling these special-order items because the big N-frame had a lot of desirable details, such as a pinned barrel, counterbored cylinder chambers, and checkering across the top strap of the frame and barrel.

Over the years, the revolver went through several name changes. In the late 1930s, the model name was changed to ".357 Magnum." Eventually, it would become known as the Model 27 when S&W started to use numeric model names in the mid-1950s.

General George S. Patton carried a 357 Magnum model and outfitted it with ivory grips and a Tyler T-grip to fill that gap between the rear of the trigger guard and front strap. He called it his "killing gun." From the 1940s through the 1960s, many FBI agents used a 3.5-inch-barrel model. J. Edgar Hoover is said to have owned one of the first Registered Magnums. Noted gun writer Skeeter Skelton was known to favor a 5-inch-barrel model. In 1994, the M27 was dropped by S&W, and wheelgun aficionados gasped with despair. Around 2009, the Model 27 was reintroduced.

In that gap when Model 27 production went dark, S&W brought out the Model 627 in 1996. Following a similar introduction as the Registered Magnum, the Model 627 is a semi-custom gun produced by S&W's Performance Center. S&W enhanced the Model 627, making it an 8-shot 357 Magnum. In 2008, another 8-shot N-frame debuted, the Model 327. These two models are direct descendants of the Registered Magnum, and these newer-generation guns offer added capacity and are constructed of different materials.

To find out how they were all put together, first we used Brownell's revolver range rod for 38/357 Service (080-617-038WB, $40) on the used 686 to check the alignment of the six chambers and the barrel. The rod slid down the barrel and into each chamber, so we were confident that the 686, though used, would still perform. We also checked the new 627 and 327, and all their chambers checked out. We used a Go/No Go 60/68 Cylinder Gauge (080-633-668WB, $36) from Brownells to check the headspace on the revolvers, which is the gap between the rear of the cylinder and recoil plate in frame. The used 686 was in spec. If the gap is too big, the revolver may misfire. The new revolvers were in spec, too. All revolvers exhibited a tight lock up of cylinder to frame. The full-size, old-style cylinder latch was loose on the 686, but a flat-blade screwdriver took care of that issue.

Two Great Makers Shoot It Out: Remington Versus Colt 45 ACPs

While the debate continues on about which firearm is the best combat handgun, the 1911 remains in the running, and, according to some, it stays at the top of the heap. The 1911 has many applications including target practice, competition, and self defense, of course.

Simple pride of ownership is never a bad reason to own a handgun, but personal defense remains the defining characteristic of the 1911 handgun. For many, the 1911 represents the best choice for repelling boarders or facing members of the criminal class.

For this task, the pistol has good features, including speed to an accurate first shot that is virtually unequaled, reliability, and accuracy. Also, the 1911 is thin enough for concealed carry. The problem is a full-size gun's profile and weight. The 1911 can be concealed effectively with proper holster selection, that isn't the question. The question is the comfort level the individual is willing to accept. For many of us, the steel-frame Commander with its -inch-shorter slide and barrel solves the problem. The Commander pistol is less likely to pinch the bottom when seated, and it is faster from the draw as well.

Reader Steven Mace of Arizona wrote us in April 2014 asking if we would consider testing a list of 1911A1 Commander-style pistols. He wrote, "If you or your staff has any experience with any of these pistols, I would appreciate any information that could be shared. Or, are there any plans to evaluate any of these pistols in the near future? My intent is to find and buy a 1911A1 for concealed carry for a person who is left-handed." His included list of desired handguns from top to bottom were the Colt XSE O4012XSE, Kimber Pro Raptor II 3200118, Para USA Black Ops Recon 96697, Remington 1911 R1 Carry Commander 96335, Sig Sauer 1911 Carry Scorpion 1911CAR-45-SCPN, Smith & Wesson SW1911SC 108483, and Springfield Armory Lightweight Champion Operator PX9115LP (September 2012, Grade A-). We evaluated a Kimber Tactical Pro II (Grade A) and a Carry Scorpion (Grade B+) in the October 2014 issue, and further honoring his request, in this installment we test the Colt XSE Commander and the Remington R1 Commander.

Some guns of this size or smaller that we've tested include the SIG Sauer 1911 C3 1911CO-45-T-C3 (Grade A) and the Rock Island Armory Tactical II Compact 51479 (Grade B) in the July 2014 issue; the Dan Wesson ECO 01969 45 ACP (Grade B+) in the September 2012 issue; the SIG Sauer 1911 C3 NO. 19GS0031 (Grade A) and the Kimber Compact Stainless II 45 ACP (Grade A-) in the August 2010 issue; the Kimber SIS Ultra (Grade B+) and Springfield Armory Loaded Ultra Compact PX9161LP (Grade B-) in the August 2008 issue; and the Smith & Wesson M457 No. 104804 (Grade B) in the September 2007 issue, among others further back.

The Colt is the top-of-the-line Commander and the Remington is a less expensive R1, which actually favored the R1 when we started because we prefer less expensive products, if they perform on par with more expensive ones. We felt the comparison was valid based upon quality, accuracy and reliability, so here's what we found.

Weatherby Mark V Deluxe 257 Weatherby

The Mark V is available in ten simple versions before you get into the custom-shop jobs. The Deluxe is the only one of these with a wood stock, and it's a fancy one. The wood on our test rifle was drop-dead gorgeous, and the stock also had excellent fine checkering and Weatherby's trademark rosewood forend cap and grip cap with white-line "maplewood" spacers. The recoil pad did not have the white-line spacer. You can get the Mark V in a dozen different standard chamberings, and more from the custom shop. The stock finish was glassy, but as we immediately noticed, not entirely level. It showed lots of waviness if you sight along its supposedly flat sides. We could feel the waviness with our fingers.

Beretta Unveils APX Striker Gun

Beretta's APX, a new striker-fired full-size pistol in 9x19mm, 9x21mm IMI and 40 Smith & Wesson cartridges, debuted at the 2015 International Defence Exhibition & Conference IDEX expo in Abu Dhabi Feb. 22.

"IDEX is one of the first venues where defense contractors present their wares to worldwide military customers and Beretta felt this was the ideal environment to present the international offering of its APX pistol," said Carlo Ferlito, general manager of Beretta and Beretta Defense Technologies (BDT) vice president.

Beretta intends to market a variant for the commercial market later this year. The new Beretta APX has an ergonomically-molded reinforced polymer frame fitted with a built-in MIL-STD-1913 Picatinny rail, interchangable backstraps and grip panels, and a modified Browning locking system. The APX is 7.56 inches long with a 4.25-inch barrel.

The trigger can be considered a light double action, with a 6-pound break, 0.2 inch of travel, and a 0.12-inch reset. The rear portion of the striker slightly protrudes from a round slot on the back of the slide as a loaded-chamber indicator.

The slide is machined from stainless steel and has a nitride coating that reduces glare, scratches, and corrosion. Other features include wide front and rear slide serrations, three-dot sights dovetailed into the slide, and no manual safety save for a Glock-style trigger safety.

Ferlito said, "Beretta waited to enter the striker-fired market until we had a pistol we knew would meet the needs of the operator. The APX has been more than three years in development. We tested it extensively with professional end users and incorporated that feedback at every opportunity. The result is a pistol platform that delivers superior performance in durability, reliability, accuracy and ergonomics."

A slot on the frame allows the use of a tool to decock it before it can be field-stripped by operating a lever found on the left side of the frame.

An optional manual safety system will be available upon request, consisting of a frame-mounted two-position switch. A reversible magazine-release catch and a factory ambidextrous slide stop/hold open release lever help make the pistol suitable for left- or right-handed shooters.

Supplied black double-stack metal magazines have polymer bottom pads and offer 17-round capacities in 9x19mm NATO and 15-round capacities in 9x21mm IMI (9 Italian) and 40 Smith & Wesson.

Springfield Armory 1911A1 Loaded .45 ACP, $565 (1999)

When we reviewed this pistol in the June 1999 issue the strikingly attractive Springfield had fully checkered wood stocks and a high polish to the sides of its blued receiver and action. The slide top and the rest of the gun was matte black. There were no plastic parts on this gun. It had a long aluminum Videki trigger, a beveled magazine well, extended safety, a skeletonized Commander-style hammer, a Novak rear sight and a highly visible front sight. The gun had a flat steel mainspring housing with vertical serrations. The beavertail grip safety had a big, hand-filling bump on the bottom, which we liked a lot. The Springfield came in a fitted plastic storage/carry case with a spare magazine, cleaning rod, and full instructions. Although it looked great, the Springfield front sight was not dovetailed into the slide. We feel dovetailing is the most foolproof, if not the best-looking, method of attaching a front sight. The Springfield had the now common front slide serrations. The top of the slide permitted easy stovepipe clearing. The Springfield's feed ramp was highly polished and the chamber throat was widened to ease feeding.

At the range, the Springfield handled all ammo with aplomb. There were no problems whatsoever. Our average five-shot group size was 2.5 inches at 15 yards, and the smallest was 1.4 inches with the Winchester hardball. This gun didn't like the Speer Lawman 230-grain FMJ, getting a 3.5-inch group as the smallest. We were quite impressed with the Springfield. In spite of its having a half-pound heavier trigger pull than the Kimber, the Springfield's pull felt lighter. There was absolutely no creep, and overtravel was minimal yet adequate. The gun felt precise.

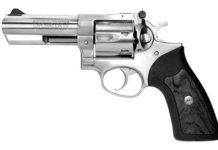

Ruger GP-100 .357 Magnum No. KGP-141 Revolver

Ruger lists seven different models in the GP100 revolver family with barrel lengths of 3, 4, and 6 inches. Finishes are either blued or stainless steel. Manufacturer's suggested retail prices range from $552 for the .38 Special +P only models to $615 for the stainless steel .357 Magnum revolvers with barrel lengths of either 4 or 6 inches. All models come with a rubber grip complete with a rosewood insert. Our 4-inch barreled KGP-141 had a pleasing bright-stainless finish and an adjustable rear sight. Elevation was the familiar clockwise for down and counter clockwise for raising the point of impact. The windage adjustment required opposite movement for changing point of impact.

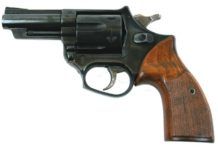

Are Used 357 Mags from Colt, S&W, and FN Worth the Money?

The 357 Magnum has an excellent reputation as a defensive round. On medium-sized game like whitetail deer at modest distances, it is effective as well. The round has been around since 1934; General George Patton carried an ivory-handled S&W 357 Mag during WWII. It is a versatile cartridge with many bullet types offered by a variety of manufacturers. Plus, 38 Special ammo in standard and +P loadings can be used in a 357 Magnum as a low-recoil alternative when training or plinking. We wanted to see if we could find a bargain in a full-size revolver with a 4-inch barrel that we could use for personal protection, and we came across two such contenders, a Smith & Wesson Model 19-4 that rated about 90 to 95 percent and a Colt Trooper MK III that rated 80 to 90 percent. Both featured 4-inch barrels, adjustable sights, and wood grips. We also came across an uncommon choice in this chambering, an FN Barracuda, available in the 1970s on a limited basis. It is unique due to the availability of an interchangeable cylinder, which could be switched between 9mm Luger and 357 Magnum. Here's more about these interesting and affordable choices, along with our recommendations.

Polymer-Frame 9mm Shoot Out: P320 Versus PPQ M2 Vs. VP9

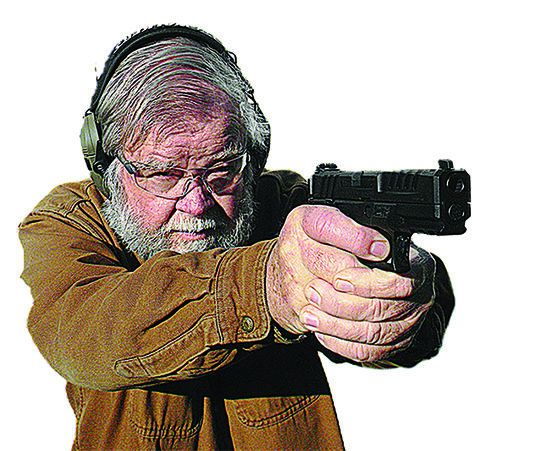

During the past few months, SIG Sauer, Walther, and Heckler & Koch have introduced pistols that feature striker-fired actions. These handguns are designed to compete for the hearts and minds of institutional buyers and concealed-carry-permit holsters as well. The improvement in rapid-fire combat shooting is provable, and absolute accuracy is improved over the original SIG P250, Walther P99 and HK P30. The question is, which handgun is the most improved and the best buy for the money — that is, the most reliable and accurate?

In this test of three 9mm striker-fired models, we were firing handguns intended for personal defense in the home, concealed carry, and practical competition. We are certain each maker is hoping to compete with Glock for institutional sales as well. At first glance, the handguns appeared similar. Each featured a polymer frame, a light rail, and similar sights. Each was relatively simple to operate. None had a manual safety as part of the design. Some features, such as the sights and the magazines, were similar. A casual shooter might sign off on all three handguns, but that isn't what we do.

Our shooters noticed the trigger actions were markedly different, and grip texturing and handling were considerably different. As the firing sessions progressed and the brass stacked up, the shoot out turned into a strong challenge between the Walther and the HK pistol. These worthy competitors traded places several times in the firing evaluations. The SIG P320 brought up the rear, in our estimation. Here's why:

GUNS, GUNS, AND MORE GUNS

Dury's Gun Shop, which supplies FFL services and guns for Gun Tests Contributing Editor Ralph Winingham in San Antonio, has partnered with Tom Gresham of Gun Talk Radio to create a limited run of 1,000 GT20 pistols, which are SIG Sauer P220 10mm handguns. Price is $1400. All GT20s will come with a SIG Sauer hard case and two eight-round magazines. Additional accessories can be purchased from Dury's and shipped directly to you with the purchase of your one-of-a-kind GT20 pistol. Shipping will only be $25 for the GT20 and free for all additional accessories ordered.

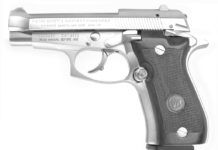

Beretta Cheetah 84 LS .380 ACP, $652

Smaller guns have always had a certain appeal. In some cases it was just the aspect of miniaturization that captures our imagination. In other cases it was the reassurance of a highly concealable weapon. One niche of such guns were semi-auto .380s, which have long been popular sidearms because of their flat, short footprint and sufficient, if not outstanding, power. Even in the small world of 9mm Shorts there is a pecking order in terms of size, with the Beretta 84LS being one of the largest.

Olympic Arms OA 98 223 Rem

The design of the OA series of AR-15 type rifles connects to the OA 98 pistol. To accommodate a folding stock, Olympic Arms developed an upper that eliminated the need for a buffer tube. However, due to subsequent legal restrictions, folding-stock models such as the OA 93 and its cousins now feature fixed stocks, but these rifles still benefit from their minimal design and lighter weight. If you look at an OA-built AR-15 and imagine it without a stock, it is easy to visualize how the OA 98 pistol came into being.